By: Anura Fernando, principal advisor and global head of medical cybersecurity, UL Solutions

Product penetration testing is fundamentally different from network penetration testing. While network penetration efforts focus on network architecture and the components on the network, product penetration testing views the product, a network node, as a system unto itself, with its own architecture and detailed design supporting and, ideally, its own defense-in-depth strategy for security by design.

While network penetration testing approaches can be adapted for product penetration testing, with regard to the electronic data interfaces, there can also be very different considerations when penetration testing at the product level, i.e., the medical device. These include the intended use of the product, use environment and usability, internal components, the product state machine and state transitions, and how product security intersects with both basic safety and essential performance. All of these factors should be considered when conducting penetration testing on a medical device.

Historically, penetration testing has been the purview of information security, and specifically focused on the cybersecurity “red team,” the offensive security team emulating an adversary. Regulators around the world have begun to recognize that managing software risks in healthcare involves more than addressing individual risks at the software unit level. It also requires tackling systemic risks that arise from the interaction of multiple factors, covering topics such as:

- Usability

- Basic safety

- Essential performance/functional safety

- Security (cybersecurity, plus physical security)

- Interoperability

- Inference of artificial intelligence (AI)

This is what led to the development of the Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation (AAMI)/UL 2800-1, the Standard for Medical Device Interoperability, which collectively addresses these many facets of systemic risk.

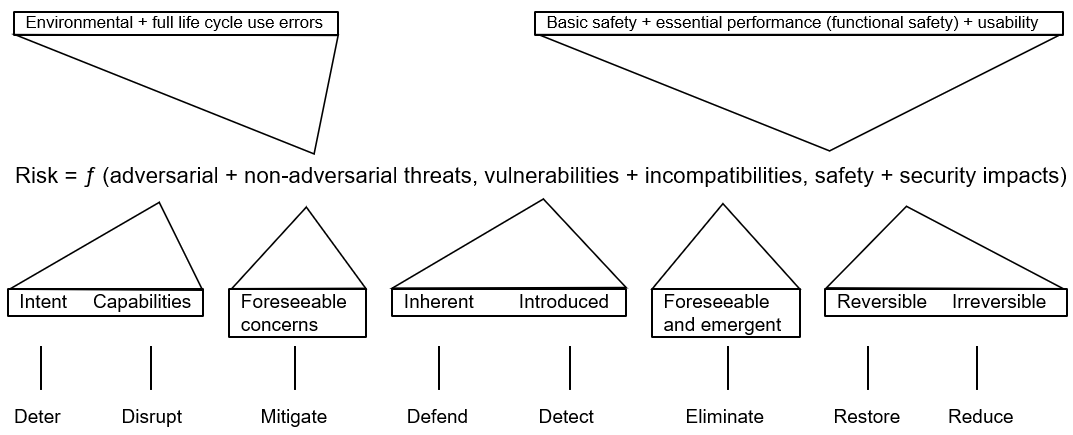

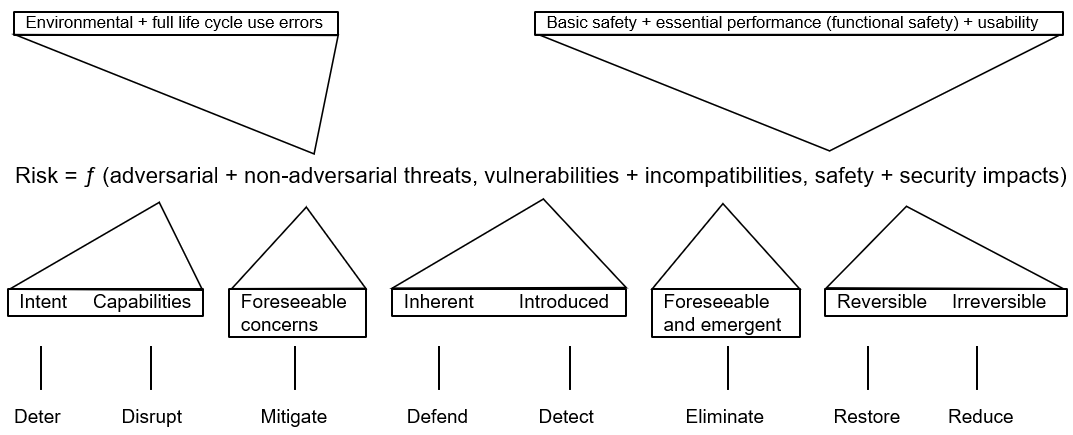

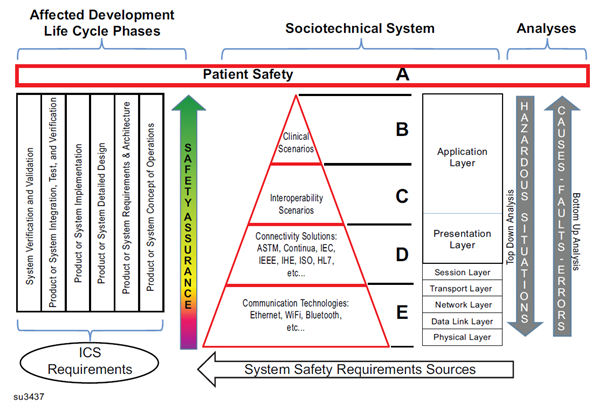

Figure 1 – Health Software System Risks

While security “red teams” are focused on adversarial attacks, penetration testing can take a much broader view to include non-adversarial threats as well. This is espoused in security risk management guidance, including NIST SP 800-30, “Guide for Conducting Risk Assessments,” which has informed standards such as:

- AAMI TIR 57, Principles for Medical Device Security — Risk Management

- IEC 81001-5-1, Health Software and Health IT Systems Safety, Effectiveness and Security, Part 5-1: Security — Activities in the Product Life Cycle

- UL 2900-2-1, the Standard for Software Cybersecurity for Network-Connectable Products, Part 2-1: Particular Requirements for Network Connectable Components of Healthcare and Wellness Systems

Non-adversarial threats commonly arise from what some standards characterize as systematic defects, or those systemic flaws that could be addressed by methodically improving the ways in which the system is being managed, e.g., either training staff not to delete critical files or removing their networked software permissions to delete files to mitigate the non-adversarial threat of accidental file deletion.

Adversarial threats, on the other hand, are often considered random occurrences or stochastic processes, where random variables may be grouped together, but many medical industry stakeholders argue that probabilistic methods should not be applied.

However, just as with non-adversarial attacks, risk controls can be implemented, but in this context, they tend to be a combination of both product-design-level controls and organizational-process-level management controls. A common area of disconnect, i.e., risk, leading to vulnerabilities in the field, i.e., in the product development or deployment environment, is when a situation arises where the process risk controls don’t translate into the implementation of product or system risk controls, e.g., the process of setting permission policies and allocating permissions to certain users isn’t implemented in the product design as an access control list (ACL).

This potential incongruity between process and product is the reason why process audits and product testing and inspection need to be conducted in tandem for improved cybersecurity outcomes. Inadvertent bias due to process overfamiliarity is why standards and best practice guidelines continue to recommend the use of third-party assessors who have not been involved in or influenced by familiarity with the product’s design and development. If an assessor isn’t independent, this can result in assessor bias and lead to assumptions and overconfidence regarding the effectiveness of the governing processes and their outputs. This, in turn, can lead to inadequate testing or improper verification of critical design features, such as security controls. This is also the reason that UL Solutions provides for the coupling of process-oriented standards, such as IEC 81001-5-1, with product-oriented standards, such as UL 2900-2-1, to serve as the foundation for certification under the Cybersecurity Assurance Program (CAP).

Three generalized approaches to penetration testing

Black box or closed box testing

In the first technique, an emulated attacker approaches the product purely as a malicious observer who has encountered the product in its natural environment and hopes to exploit it in some way for a particular gain, such as:

- Financial reward

- Fame

- Political objectives

- Entry point for lateral movement

White box or open box testing

The second approach is diametrically opposed to the first — and this is where all the architectural and detailed design information regarding the product, components and the relevant aspects of its environment is made available to the emulated attacker to optimally facilitate exploitation of the product by reducing the resource-intensive information gathering or surveillance phase of the attack.

Gray box, translucent or application programming interface (API) testing

The third approach is a hybrid of the first two, which begins with establishing a minimal baseline of information regarding the product, components and environment that would allow for initial identification of specific targets with subsequent attack vectors formulated for those specific targets as either attack milestones or final objectives.

Since the first two approaches are so different in their basic nature, unique threat information can be gathered from each of them, which may be valuable to understanding how to protect the product. Therefore, it is advisable to use a combination of the first two approaches to best leverage the unique aspects of each. However, if this is not feasible from a resourcing perspective, the third can be a satisfactory compromise.

Security testing in support of penetration testing objectives

Static Application Security Testing (SAST) — This type of testing can be semiautomated for gathering information that can serve as inputs to penetration testing. It is referred to as static because it analyzes source code or binaries of software components in their initial release state, e.g., human-readable source code or machine-readable installation images, meaning not “actively” executing or interacting with other software components or associated hardware.

Dynamic Application Security Testing (DAST) — This is a different type of testing that can semiautonomously gather different types of information than SAST, which can then also serve as inputs to penetration testing. It is referred to as dynamic because it analyzes functional attributes of actively executing software, e.g., possible anomalous behaviors, interactions among multiple software components, etc.

A fundamental tenet of security is that an asset only needs to be secure enough to make the cost of compromising the asset greater than the value of the asset. So, by corollary, penetration testing should only be considered complete when either the asset has been compromised or the resources available for attempting to compromise the asset have been exhausted.

Threat modeling

Understanding the assets to be protected and the environment within which those assets exist is one of the most important prerequisites for penetration testing. Many people who deal with security in the healthcare sector automatically — and unfortunately often exclusively — think of personally identifiable information (PII) and protected health information (PHI) as the only assets to be protected in health informatics applications. This is a common misconception that can have very serious consequences if not corrected.

While it is true that PII and PHI need to be secured, there may be potentially much more safety-critical data, such as command-and-control data, and much more security-critical data, such as keys and tokens, which, if compromised, could lead to direct and immediate physical harm to the patient or to many patients at once. Therefore, understanding the entire system and establishing a good asset inventory is a great way to begin building a threat model.

Threat modeling should be an iterative process that spans the various life cycle phases of the product that can be managed within the context of a Secure Product Development Framework (SPDF). For example, relatively early in the product’s life cycle, the intended use may be fairly well understood, but implementation or design details may not be. Therefore, threat models, asset inventories, etc., should be considered living documents and not just one-time artifacts created for compliance purposes.

A robust threat model would describe system entities, such as:

- Processes

- Stores

- Actors

- Data flows with associated metadata

- System and entity boundaries, including established trust boundaries

Any of these may be considered assets, depending on the circumstances. These fundamental model attributes would be constructed to reflect a global system view, multi-patient harm view, updateability/patchability view and security use case view.

Methodology

Many medical device manufacturers have been hoping for a silver bullet that can quickly, easily and economically address penetration testing needs. Unfortunately, some tool vendors offer what they claim to be such single “silver bullets,” but so far, there is no single quick test or automatic scan that can adequately address the plethora of attack vectors that may be associated with even a relatively simple attack surface like a serial communication interface.

Penetration testing typically starts with the attacker gaining an understanding of the attack surface. A critical prerequisite is an understanding of the asset to be compromised, since gaining unauthorized access to the asset is the end goal. Sometimes an asset may not be intuitive. For example, an inexperienced and unskilled hacker, also known as a script kiddie, may only seek access to the internal network of a well-known security company for notoriety. In this example, the asset to be protected is the security company’s brand reputation rather than a specific piece of information or data within the company. However, the identification of this kind of asset may be less intuitive than a readily recognizable asset, such as the financial tokens in a bank account.

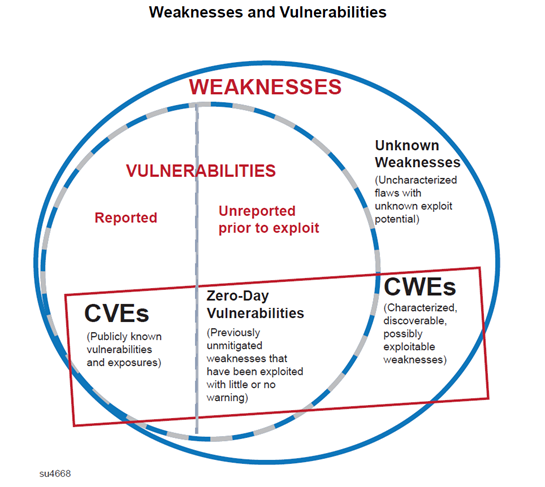

Since vulnerabilities arise from weaknesses in the product’s design, it is important to understand what weaknesses or even known vulnerabilities may be present in the product’s constituent components that are:

- Obtained as commercial off-the-shelf software (COTS)

- Obtained as free and open-source software (FOSS)

- Developed by the medical device manufacturer and integrated into the product

The following figure from the UL 2900-1 Standard depicts the life cycle of a vulnerability from its origins as a design weakness to its final disposition as a common vulnerability and exposure to be patched and removed from existence:

Figure 2 – Weakness to Vulnerability Life Cycle (Source: UL 2900-1)

It is important to recognize that such weaknesses can stem from a variety of sources, such as:

- Microelectronics

- Hardware

- Firmware

- Software

- Hardware-to-hardware interfaces

- Hardware-to-software interfaces

- Software-to-software interfaces

- User interfaces

- External interfaces

These factors can be unknown entities outside of the scope of what is defined as the product and even from software development and management processes, including post-deployment use and decommissioning.

The core issue is that health software systems integrate multiple software components that must communicate and interact seamlessly. Therefore, interoperability concerns communications between software items or the components within a sociotechnical health software system. The failure of such communications can potentially result in increased risk to patients, as depicted by the following diagram from AAMI/UL 2800-1:

Figure 3 – Interoperability in Health Software Systems (Source: AAMI/UL 2800-1)

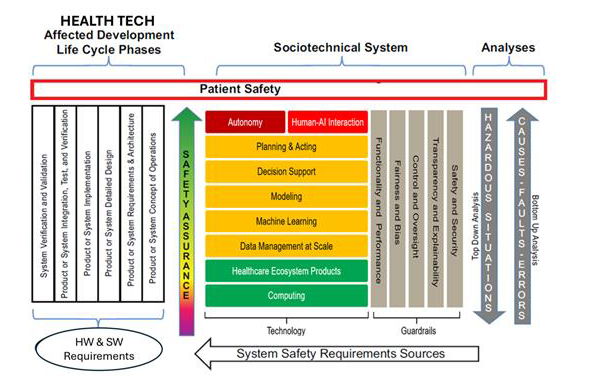

This sociotechnical communication system serves as the platform upon which to build a plethora of healthcare applications, along with their underlying enabling technologies. This has already been seen with the evolution of the internet, cloud computing, machine learning (ML), and most recently, generative AI. What all of these have in common is that they are all predicated on functionality defined by software. Thus, even when characterizing a relatively new software technology like generative AI, we can see that the need for surrounding processes and guardrails can be similar. However, entirely new types of risks could be introduced and would need to be addressed based on the functionality and complexity of the software, such as text-based vs. multimodal generative AI, or the distributed nature of agentic AI.

The safety and security aspects of such complex software systems can be viewed through the lens of different levels of software abstraction, as can be seen in this adaptation of the AAMI/UL 2800-1 interoperability risk management process to a generalized AI technology stack, applying guardrails from UL 3115, the Outline of Investigation (OOI) for Safety of AI-Based Products.

Figure 4 – Interoperability Risk Management for AI (adapted from AAMI/UL 2800-1)

Analyzing risks of both the AI components that enable functionality and the guardrails that protect that functionality are equally important. This can be seen when examining the annually revised technological weakness lists identified through initiatives such as the SANS Common Weakness Enumeration (CWE) Top 25, MITRE Adversarial Tactics and Techniques for AI Systems (ATLAS™), and the Open Web Application Security Project (OWASP). In 2024-2025, OWSAP found the top 10 most prevalent weaknesses in ML and AI to involve:

| Top ML weaknesses | Top AI weaknesses |

|---|---|

| Input manipulation | Prompt injection |

| Data poisoning | Sensitive information disclosure |

| Model inversion | Supply chain |

| Membership inference | Data and model poisoning |

| Model theft | Improper output handling |

| AI supply chain | Excessive agency |

| Transfer learning | System prompt leakage |

| Model skewing | Vector and embedding weaknesses |

| Output integrity | Misinformation |

| Model poisoning | Unbounded consumption |

The penetration testing methodology outlined in UL 2900 for any health software, whether a simple embedded state machine or a complex AI inference model, is predicated on exercising software quality. This includes testing the robustness of the guardrails implemented in code and architecture that result from the medical device quality management processes, such as the SPDF.

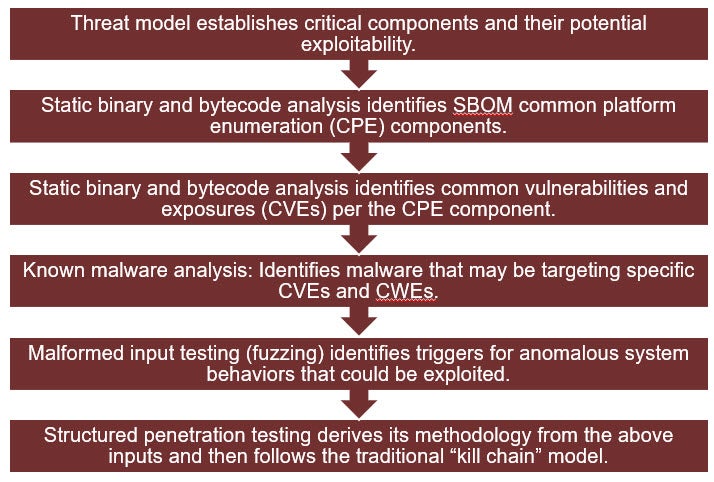

Figure 5 – UL 2900 Penetration Testing Methodology

The threat model, as described earlier, is the key to the entire security risk profile of the product or system. Static binary and bytecode analysis identifies the software components, such as the composition of the software, plus any known vulnerabilities that may be associated with those components. Static source code analysis identifies weaknesses, using sources such as OWASP, that may be entirely new, arising as a function of developing the unique new components of the product or system or making post-release modifications to the software. Known malware analysis identifies the presence in the product of any known malware that may have already been potentially introduced through the development tool chain or when software libraries or other development collateral may have been downloaded from the internet during the development process. Finally, malformed input testing (also known as fuzzing) introduces statistically proven randomized stressors to external product interfaces to repeatably and reproducibly evoke anomalous behaviors or those counter to security and safety. These results may then be leveraged during structured penetration testing, along with the outputs of the preceding information-gathering steps, to either successfully exploit the assets or demonstrate the adequacy of the security controls.

When performed under the CAP Scheme, this testing would demonstrate the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) penetration testing recommendations to establish:

- Independence and technical expertise of testers

- Scope, duration, methods and results of testing

- Assessment of findings and rationales for deferring or not implementing mitigations

Penetration testing regulatory environment

There is increasing commonality around the world as industrywide understanding improves regarding principles behind penetration testing. This can be seen, for instance, when comparing the FDA software guidance documents with the software requirements of the European Union (EU) Medical Device Regulations (MDR) and associated harmonized and soon-to-be-harmonized standards. This is due to coordination efforts by organizations such as the successor to the Global Harmonization Task Force (GHTF), known as the International Medical Device Regulators Forum (IMDRF), one of many global entities that has recognized the value in the security testing approaches of UL 2900 through reference in their guidance documents.

In 2023, the FDA first established a clear linkage between cybersecurity and interoperability under Amendment 524B to the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act in their guidance document, “Cybersecurity in Medical Devices: Quality System Considerations and Content of Premarket Submissions – Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff.” This was reflected in Canada as well through their co-deployment with the FDA of an Electronic Submission Template and Resource (eSTAR), which clearly illustrates the relationships among regulatory expectations for software quality, cybersecurity and interoperability.

The EU MDR has similar linkages within embodied regulations involving software and interoperability, as well as through the cross-referencing of applicable ancillary EU regulations, such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the Network and Information Security (NIS) Directive, and the Cybersecurity Act (CA). While there are certain differences due to operational processes in the decentralized regulatory model of the EU versus the centralized regulatory model of the U.S., which leads to variations in enforcement of jurisdictionally defined security-related issues like privacy, e.g., GDPR in the EU and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) under the Office of Civil Rights (OCR) in the U.S., the broad security aspects are very well-aligned. In part, this comes through global standardization efforts, and sharing of information and alignment of concepts across standards — such as IEC 81001-5-1, which is soon to be harmonized in the EU, thus carrying a presumption of conformity to aspects of their regulations, and UL 2900 — which can help support innovation in testing through EU membership in IMDRF and alignment with its guidance.

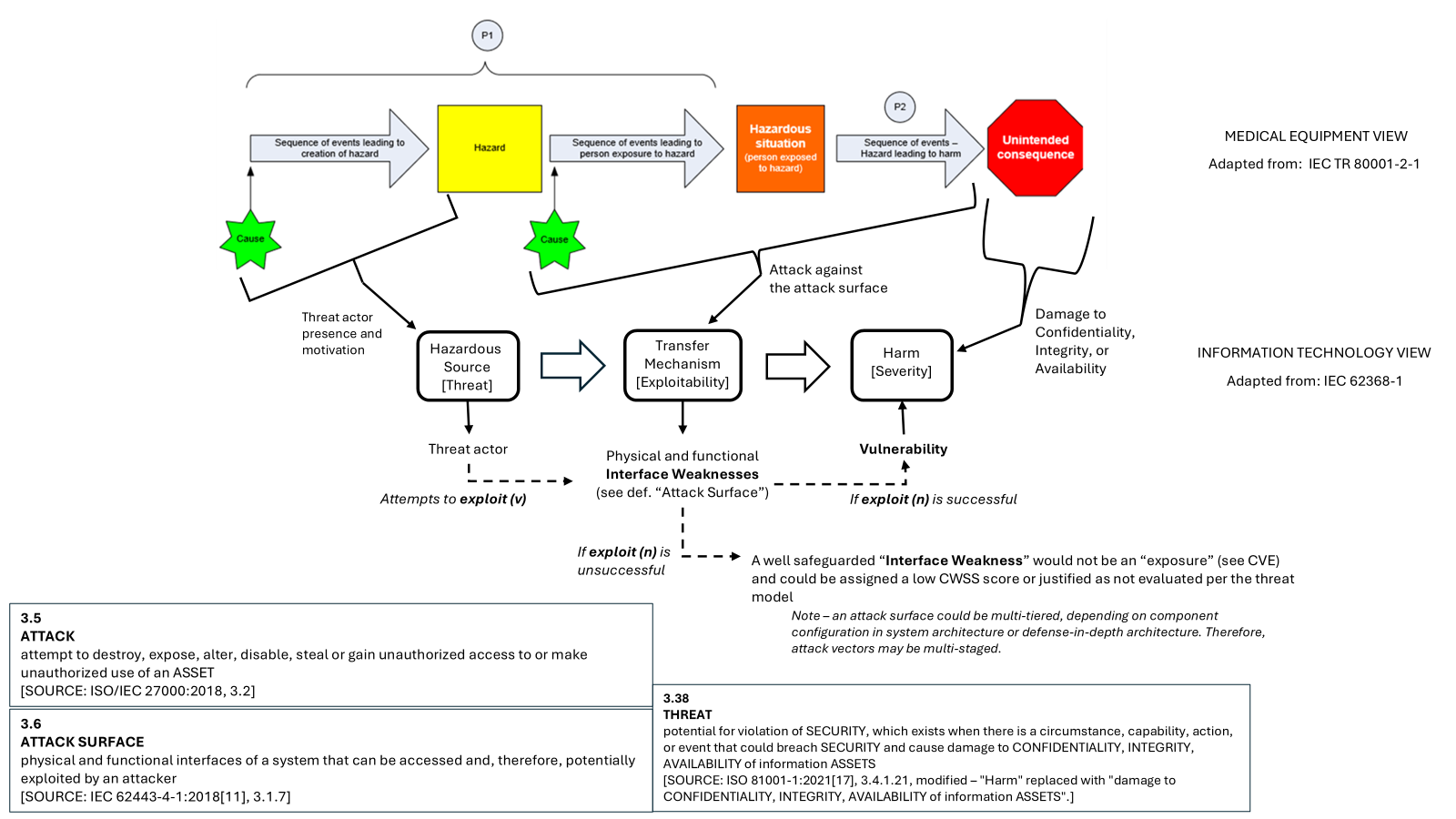

Some of the technical corollaries for penetration testing can be seen in the following illustration of how a cyberattack could be viewed through the lens of standards that are either already harmonized or pending harmonization. These include IEC 62368, Audio/Video, Information and Communication Technology Equipment — Part 1: Safety Requirements, and IEC 81001-5-1 (for the attack-related terminology), as well as the broader medical device risk management process adapted from IEC Technical Report 80001-2-1, Step by Step Risk Management of Medical IT-Networks; Practical Applications and Examples.

Figure 6 – Standards-Based View of a Medical Cyberattack

Thus, we can see that the foundations of the Medical Cybersecurity Assurance Program (Medical CAP) in leveraging IEC 81001-5-1 as well as UL 2900-2-1 for either product certification or for discrete penetration testing are intended to satisfy the cybersecurity expectations of a diverse set of global stakeholders — from regulators to purchasers to patients.

Penetration testing of medical devices and health software systems serves purposes beyond cybersecurity. It helps identify software quality problems, AI/ML weaknesses and systemic defects in interoperability that could result in loss of confidentiality, integrity, availability, reputation and, most importantly, patient safety.

Are you interested in penetration testing for your product(s)?

UL Solutions offers various penetration testing services, from testing aligned with current standards to custom penetration testing, developed to fit your needs. Our tests target critical device software functions and components, including hardware. Contact us to discuss how we can support your system or product security strategy.