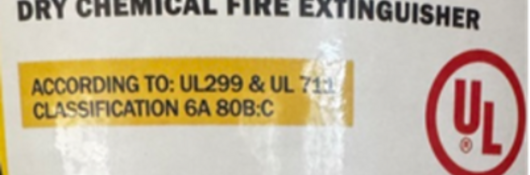

As a global safety science leader, UL Solutions helps companies to demonstrate safety, enhance sustainability, strengthen security, deliver quality, manage risk and achieve regulatory compliance.

See how we put safety science to work to help create a safer, more secure and sustainable world for you.

Explore our business intelligence-building digital tools and databases, search for help, review our business information, or share your concerns and questions.

A secure, online source for increased visibility into your UL Solutions project files, product information, documents, samples and services.

Access UL certification data on products, components and systems, identify alternatives and view guide information with Product iQ.

- Automotive and Mobility

- Building Technologies and Construction

- Chemicals and Materials

- Data Centers

- Energy and Utilities

- Financial and Investment Services

- Government Services

- Health and Life Sciences

- Industrial Products and Systems

- Life Safety and Security

- Retail Ecosystem

- Technology and Electronics

- Products and Components

- Software and Products

Introducing ULTRUS™

ULTRUS™ helps companies work smarter and win more with powerful software to manage regulatory, supply chain and sustainability challenges.

Featured Products

News

Read the latest news about our efforts to help make the world safer, more secure and more sustainable.

Contact our media team